Development Inequalities | Angola

In the decade following Angola’s long and brutal civil war, the country struggled not necessarily to “rebuild” but, effectively, to build from scratch both the physical and political infrastructures of a peaceful, independent country. Believing democratization and good governance essential to peace and stability, intergovernmental and international non-governmental organizations rushed to the country to support these efforts. While they often hired local and returning Angolans to implement the projects, “international” staff often led the projects as well as managed the “national” or “local” staff. These classifications—“international,” “national,” “local,” and the like—came with a set of presumptions all staff acted to fulfill and a set of limitations to which they were held.

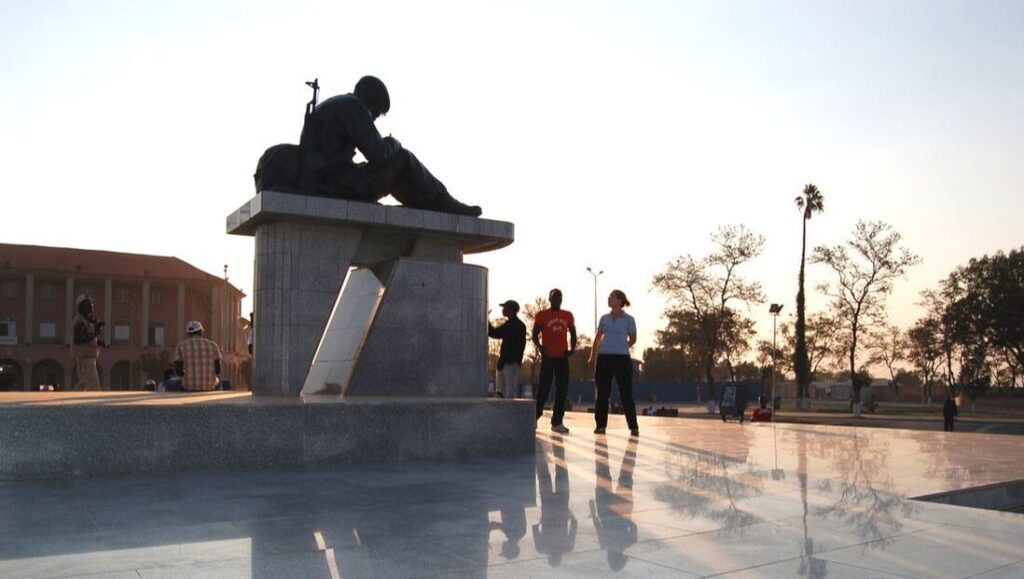

Between 2005 and 2015, I completed ethnographic fieldwork in Luanda, Huambo, and Bié Provinces, examining the experiences of in-country development and humanitarian aid professionals in a post-war democratization program. Rather than approaching this research through the typical development “encounter” between agents and intended beneficiaries, my research explored the internal logics of the development industry: the various logics that drive organizations and the experiences of both local and international staff.

Ultimately, I argue, these institutions replicate and reproduce many of the same global inequalities they seek to combat.

I have shared many of my findings from this research in various academic journals. These articles examine themes such as:

- Professional distinctions between “local” or “national” and “international” staff

- The experiences of transnational professionals

- Interpretative labor and policy execution at the community implementation levels

- The logics underpinning monitoring and evaluation as a staple in development NGOs’ operations

These and more articles can be accessed here.

My book, Implementing Inequality, builds on these themes, focusing on how institutional categories in development organizations formalize unequal privilege within the industry.

In the book, I examine how common bureaucratic practices such as monitoring and evaluation programs or logframe analysis obscure and frustrate the on-the-ground work of implementation agents (the “implementariat”), rendering them an inferior class of professionals and undermining their efforts. Underestimating the intense relational work of the implementariat, development sabotages itself and must revisit how to assess its work and workers.

Read more about the book here.